by Martin Maisel

(photos used with appropriate permission)

Part 5

Aeronca

“Unlike other light plane makers, Aeronca was not so much the product of a single formative aviator or family, but the product of many….” (Aeronca/Champion History – Beyond the Bathtub, by Richard Harris)

The beginnings of Aeronca can be traced to French-born Jean Alfred Roché (1894-1977). Roché received a Master’s Degree in Engineering, with honors, from Columbia University and worked as an airplane designer throughout his career. While still a teenager, Roché, showing an early interest in aviation, made several successful flights in a glider.

After college Roché worked for a short time as a Designer at the Huffington Aircraft Company, Garden City, New York, and as an Assistant Chief Engineer at the Standard Airplane Company, in Plainfield, New Jersey. In 1917 he accepted a position of Chief Engineer with the Materiel Division of the U.S. Army Air Corps at McCook Field (later Wright-Patterson Air Force Base). McCook Field was the site of the first United States military aviation research center. Roché would spend the remainder of his career in the service of the government, becoming the Head Aeronautical Engineer of the U.S. Army, and later U.S. Air Force Material Command and Technical Advisor to the N.A.C.A. Langley Research Center. He retired in 1960.

After college Roché worked for a short time as a Designer at the Huffington Aircraft Company, Garden City, New York, and as an Assistant Chief Engineer at the Standard Airplane Company, in Plainfield, New Jersey. In 1917 he accepted a position of Chief Engineer with the Materiel Division of the U.S. Army Air Corps at McCook Field (later Wright-Patterson Air Force Base). McCook Field was the site of the first United States military aviation research center. Roché would spend the remainder of his career in the service of the government, becoming the Head Aeronautical Engineer of the U.S. Army, and later U.S. Air Force Material Command and Technical Advisor to the N.A.C.A. Langley Research Center. He retired in 1960.

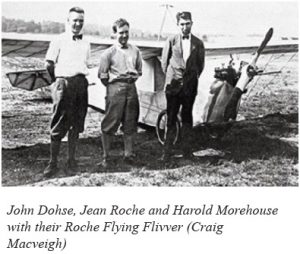

Aviation was not only Roché’s vocation, it was his passion. On his own time, in the early 1920s, he worked on designing a small light plane that would make flying practical and safe for the average person. His goals for this airplane included a low initial cost, low operating costs, and inherent stability. In 1925, with his friend John Quentin Dohse, the Roché-Dohse Company was formed to develop and market his “Flying Flivver”. However, without adequate funding they made little progress.

In 1927 Charles Lindbergh’s successful trans-Atlantic solo flight stirred up a national aviation craze. The exploding interest in aviation drew the attention of businessmen and investors nationwide. Robert A. Taft, the son of former U.S. President William Howard Taft and later to become a U.S. Senator, invested in a venture being promoted by the Lunken family who owned and operated an airport in Cincinnati, Ohio. Incorporated in 1928, the Aeronautical Corporation of America was founded, with the intention of building and selling light airplanes – but they had absolutely nothing “aeronautical” to sell.

In their search for an “aeronautical” product, the Lunkens were introduced to Roché who had an airplane design, but no way to bring it to market. Roché’s credentials as chief civilian engineer at the Army’s McCook Field gave him credibility and, coupled with the simplicity of his airplane design, it appeared to be just what the Lunkens were looking for.

With a simple triangular fuselage structure and fabric-covered wire-braced wings, the single-place Flying Flivver was among the first to use the versatile Clark*-Y airfoil. Designed by Roché and his McCook Field colleague John Q. Dohse, the tiny single-seat airplane, powered with a 26 horsepower Morehouse** O-80 engine, was a gentle, well-mannered craft, stable and easily mastered, landing at 30-35 mph, and cruising at 50-60mph.

With a simple triangular fuselage structure and fabric-covered wire-braced wings, the single-place Flying Flivver was among the first to use the versatile Clark*-Y airfoil. Designed by Roché and his McCook Field colleague John Q. Dohse, the tiny single-seat airplane, powered with a 26 horsepower Morehouse** O-80 engine, was a gentle, well-mannered craft, stable and easily mastered, landing at 30-35 mph, and cruising at 50-60mph.

In exchange for the sale of his design to the Aeronautical Corporation of America (later shortened to Aeronca) Roché received shares of company stock and seat on the board of directors, along side of Robert Taft and other major investors.

The original configuration of the flying Flivver was not suitable for mass production, so Aeronca hired Roger Schlemmer, a recent graduate of the University of Cincinnati’s aeronautical school, to re-design the airframe while McCook Field engineers Roy Poole and Robert Galloway crafted a production version of the engine.

The original configuration of the flying Flivver was not suitable for mass production, so Aeronca hired Roger Schlemmer, a recent graduate of the University of Cincinnati’s aeronautical school, to re-design the airframe while McCook Field engineers Roy Poole and Robert Galloway crafted a production version of the engine.

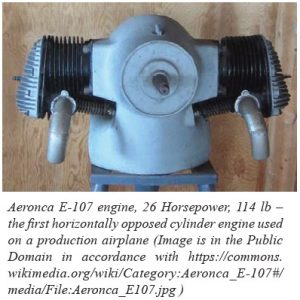

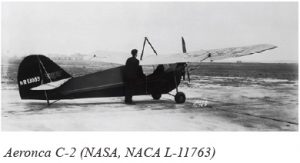

The revised engine, labeled the E-107, was quite reliable for its time, having a 400 hour TBO (Time Between Overhauls). With that engine Aeronca had the distinction of being, perhaps, the only light aircraft manufacturer that also produce the aircraft’s powerplant. The resulting first product of Aeronca was designated the C-2 Scout and arrived on the scene in 1929 – just as the stock market collapsed.

The revised engine, labeled the E-107, was quite reliable for its time, having a 400 hour TBO (Time Between Overhauls). With that engine Aeronca had the distinction of being, perhaps, the only light aircraft manufacturer that also produce the aircraft’s powerplant. The resulting first product of Aeronca was designated the C-2 Scout and arrived on the scene in 1929 – just as the stock market collapsed.

While the economic depression hit most airplane manufacturers hard, the cheap homely little Aeronca, jokingly known as the “Flying Bathtub”, flourished. In just two and one-half years over 160 were sold – becoming America’s first successful “personal” airplane.

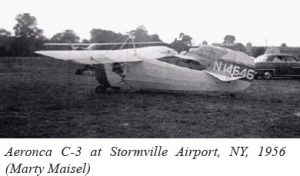

When sales of the C-2 began to fade, Aeronca recognized that its customers wanted a two-place airplane. Sport pilots wanted to carry a passenger and financially-strapped flight schools needed a cheap (to buy and operate) trainer. The response was the C-3 Collegian.

When sales of the C-2 began to fade, Aeronca recognized that its customers wanted a two-place airplane. Sport pilots wanted to carry a passenger and financially-strapped flight schools needed a cheap (to buy and operate) trainer. The response was the C-3 Collegian.

The general configuration of the C-2 was retained, but to accommodate the two seats the fuselage was widened. The additional loading also required the engine power to be increased. The modified two-cylinder, single-ignition engine was now rated at 40 hp and was designated the E-113.

The general configuration of the C-2 was retained, but to accommodate the two seats the fuselage was widened. The additional loading also required the engine power to be increased. The modified two-cylinder, single-ignition engine was now rated at 40 hp and was designated the E-113.

Over 430 C-3 aircraft were sold, firmly establishing Aeronca as a key player in the light aircraft business. But competition (from the Piper Cub, for example) and changes in Government regulations would bring an end to the production of the C-3 in 1937. It was clear that the C-3 lacked certain amenities, like comfort, good visibility, and dual controls. Superior competitors were appearing.

By the mid-1930s the U.S. Civil Aeronautics Administration (the CAA, predecessor of the FAA) introduced new regulations concerning the design of certificated aircraft. Among other stipulations, these rules prohibited the use of wire bracing as the only supports for the wings and required that engines be equipped

By the mid-1930s the U.S. Civil Aeronautics Administration (the CAA, predecessor of the FAA) introduced new regulations concerning the design of certificated aircraft. Among other stipulations, these rules prohibited the use of wire bracing as the only supports for the wings and required that engines be equipped

with dual ignition systems. The C-3 was no longer a viable product.

New aircraft designs would have to be different, but the original designers had wandered away and, after a 1937 flood wiped out the contents of the Aeronca factory at Lunken airport, Aeronca’s aging owners decided to sell the company to Walter Friedlander, an Ohio real estate tycoon. Friedlander bought the company to set up his sons in the airplane business.

Under the new management, with Roger Schlemmer now as Aeronca’s chief engineer, they took on the challenge of modernization. Based on the need to meet new regulations and on known issues with the earlier design, Schlemmer switched to a strut-braced wing, a wider landing gear with oleo struts, and provided a more comfortable cabin with better visibility.

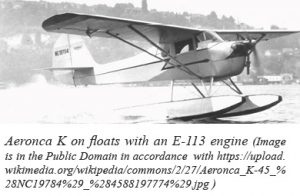

When production started in 1937 Aeronca K’s were powered by the single ignition two-cylinder Aeronca E-113 engine. To meet the 1938 CAA mandate, a dual ignition version of the E-113 engine was introduced but it had reached the limit of its growth capability. Aeronca also offered the K with the four-cylinder Continental A-40 engine. Before ceasing production in 1938, 357 K models were built.

When production started in 1937 Aeronca K’s were powered by the single ignition two-cylinder Aeronca E-113 engine. To meet the 1938 CAA mandate, a dual ignition version of the E-113 engine was introduced but it had reached the limit of its growth capability. Aeronca also offered the K with the four-cylinder Continental A-40 engine. Before ceasing production in 1938, 357 K models were built.

With the development of suitable four cylinder engines from manufacturers like Continental, Franklin and Lycoming, Aeronca decided to get out of the engine manufacturing business.

As higher horsepower versions of four cylinder engines became available, Aeronca continued to modernize and improve their products. The next major model developed in 1938 was the Aeronca 65C Chief, powered by the Continental A-65 (65 hp) engine. That design evolved into the military O-58/L-3 Grasshopper used in WWII. Over 650 civilian models and nearly 1500 military versions were produced.

During the war Aeronca was tasked by the government to build other planes, such as the Fairchild PT-19 trainer. While this work brought in more money, it also kept Aeronca confined to tube-and-fabric planes with wood-spar wings. That technology was rapidly becoming obsolete and the company was left behind other manufacturers who were proficient in aluminum aircraft construction by the end of the war.

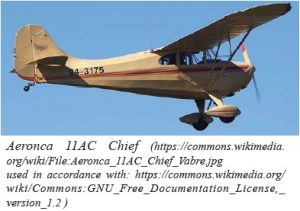

Postwar production included the tandem 7AC Champion and the side-by-side 11AC Chief. Between 1945 and 1951 nearly 8,000 Champions were manufactured.

Postwar production included the tandem 7AC Champion and the side-by-side 11AC Chief. Between 1945 and 1951 nearly 8,000 Champions were manufactured.

As many other light airplane manufacturers experienced, the winds of fortune changed for Aeronca. Light aircraft production ceased in 1951 and the company changed hands several times, remaining in the aviation business, and occasionally producing aircraft or aircraft components. Aeronca Inc. is currently a division of Magellan Aerospace.

As many other light airplane manufacturers experienced, the winds of fortune changed for Aeronca. Light aircraft production ceased in 1951 and the company changed hands several times, remaining in the aviation business, and occasionally producing aircraft or aircraft components. Aeronca Inc. is currently a division of Magellan Aerospace.

In its time, Aeronca was one of the giants of the light aircraft industry.

Disclaimer: The biographical information presented in this series was obtained primarily from multiple internet sources. As may be expected, the data provided by these sources were, in a few instances, inconsistent. In spite of the possibility that some minor points in these stories might not prove to be historically accurate, the biographies are believed to be substantially true. In any case it is clear that the individuals described in these biographical notes played important roles in the development of the light aircraft industry in the United States and their contributions should not be forgotten.

A comprehensive listing of American aircraft manufacturers can be seen here.