by Martin Maisel

(photos used with appropriate permission)

Walter Beech

Walter Herschel Beech was born in Pulaski, Tennessee, on January 30, 1891. Walter attended public school but did not progress beyond the sixth grade. What he lacked in formal education, however, he made up for with his love of reading and his instinctive technical abilities.

His interest in aviation showed up early and, in 1905 at the age of 14, he attempted to build a glider of his own design. Although the glider was a failure, it didn’t deter him from his dream of flight. Beech’s mechanical talents led to a job as an apprentice automobile mechanic in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 1911. His adeptness in maintaining automobile engines and his newly acquired chauffeuring skills soon put him in demand among automobile-owning financial executives in that city.

In 1914, Beech and a friend bought a damaged Curtiss biplane. After making all the necessary repairs he, like Clyde Cessna, taught himself how to fly. By 1916 he was an accomplished aviator, having accumulated many hours aloft in his repaired Curtiss aircraft. When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Beech joined the U.S. Army Air Corps and served as an aircraft engine mechanic.

When the Armistice was signed in 1918, Beech decided to remain in the Army. He was chosen as a pilot candidate and became an enlisted airman in October 1919. However, due to air service funding cuts dictated by a peace-minded Congress, Beech’s Army service was soon terminated.

Walter Beech, now out of work, approached Art Hill who operated an automobile repair shop in Arkansas, Kansas, seeking employment. As an indication of Beech’s financial state at the time, after he was hired Beech asked Art to advance him money, so that he could buy breakfast before starting work the next day. Before long Beech bought an “old” Army surplus biplane in need of repairs. Art Hill allowed him to put the airplane in his shop

while Beech and his friends restored it to flying condition. Recollections of local residents indicate that Beech intended to use that aircraft to barnstorm – a popular activity for ex-military pilots during that time.

In 1920 Beech joined the Williams & Hill Aeroplane Company of Arkansas, Kansas, and, during the summer, took passengers on local sightseeing flights from the landing field north of the city. In December 1920 the Williams–Hill Airplane Company (note the slight difference in the company name, as reported in the local newspaper) put on a “big air frolic,” an early fly-in and air show, for which flyers within a radius of 200 miles were invited to attend. One attraction was a “machine designed by Walter H. Beech, engineer and designer for the Williams-Hill Company.” The newspaper article continues with “The purpose of the flying frolic is to raise funds for the local company with which to erect hangars on the field north of the city.”

Historic records are unclear about what happened next, but there are reports that a hangar, perhaps the one built with proceeds from the air frolic, and where Beech and a few other local pilots stored their aircraft, burned down. The fire was fed, in part, by a drum of volatile dope. The story, as remembered by local residents, was that “Walter Beech approached businessmen in town for $500 to replace the hangar, saying that he wanted to build airplanes there – they laughed at him. That’s when he went to Wichita”.

In 1921, now in Wichita, Beech was hired by “Matty” Laird as a test and demonstration pilot and salesman for the E.M. Laird Aviation Company, producers of the Laird Swallow biplane. Beech continued to hone his piloting skills, and within a year had established a reputation throughout the Midwestern states as a daredevil aviator. To prove the reliability and performance of the Swallow, Beech entered, and won, numerous races.

In 1921, now in Wichita, Beech was hired by “Matty” Laird as a test and demonstration pilot and salesman for the E.M. Laird Aviation Company, producers of the Laird Swallow biplane. Beech continued to hone his piloting skills, and within a year had established a reputation throughout the Midwestern states as a daredevil aviator. To prove the reliability and performance of the Swallow, Beech entered, and won, numerous races.

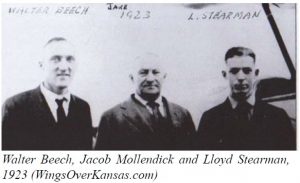

When Matty Laird left the company and sold all of his rights to financier Jacob Mollendick, the company was renamed the Swallow Airplane Manufacturing Company. Walter Beech was given increased responsibilities, eventually becoming the general manager of the company. With fellow employee Lloyd Stearman, a proposal to improve the structure of the Swallow by changing the wood fuselage to a steel tube design was presented to their boss. Mollendick would hear nothing about changing the established design of the Swallow. His response to Beech’s and Stearman’s proposal

was typical of the cantankerous Mollendick, and, in 1924, the two young employees decided to leave Swallow and start an airplane company of their own.

Beech and Stearman approached a well-known local aviation figure, Clyde Cessna, to join them in the new venture. Cessna had gained his reputation as one of the first aviators and aircraft builders in the region, and had run a successful flying exhibition business. Cessna was named as president of the new Travel Air Manufacturing Company, and provided both business leadership as well as financial support. With the key individuals in place, the Travel Air Company was established in February 1925.

Beech and Stearman approached a well-known local aviation figure, Clyde Cessna, to join them in the new venture. Cessna had gained his reputation as one of the first aviators and aircraft builders in the region, and had run a successful flying exhibition business. Cessna was named as president of the new Travel Air Manufacturing Company, and provided both business leadership as well as financial support. With the key individuals in place, the Travel Air Company was established in February 1925.

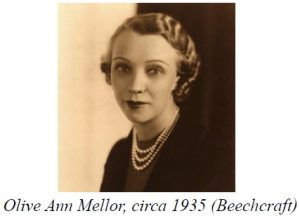

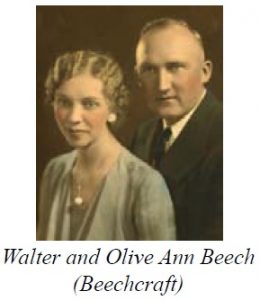

Stearman, having some formal engineering education would be the chief engineer and Beech, with his mechanical skills, took over the manufacturing aspects of the company. The twelfth employee hired by Travel Air was secretary and bookkeeper, Olive Ann Mellor, the only non-pilot in the company at that time.

Stearman, having some formal engineering education would be the chief engineer and Beech, with his mechanical skills, took over the manufacturing aspects of the company. The twelfth employee hired by Travel Air was secretary and bookkeeper, Olive Ann Mellor, the only non-pilot in the company at that time.

The initial design that rolled off of Stearman’s drafting board was a biplane, originally labeled the Model A. Successive models were available with alternate wing designs and provided increased performance with an array of higher horsepower engines. (Later the Model A series was designated the Travel Air 1000, the Model B called the Travel Air 2000, etc.) By the way, the fuselage and tail structures of all Travel Air aircraft used steel tubing, as they had proposed for the Swallow aircraft. Like most planes of the day, the wings had wood spars and ribs and were fabric covered.

Within a year Stearman left Travel Air to start his own aircraft company in California. But, with the customer’s ability to select the aircraft configuration that suited their needs, along with a growing reputation for good performance, ruggedness and high reliability, business continued to expand. By August of 1928 Travel Air aircraft accounted for just over 50% of Department of Commerce license applications.

Within a year Stearman left Travel Air to start his own aircraft company in California. But, with the customer’s ability to select the aircraft configuration that suited their needs, along with a growing reputation for good performance, ruggedness and high reliability, business continued to expand. By August of 1928 Travel Air aircraft accounted for just over 50% of Department of Commerce license applications.

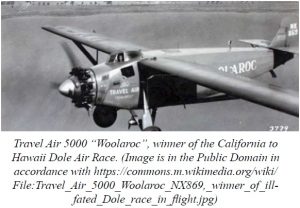

Clyde Cessna had, for some time, been unsuccessful in persuading Beech to develop a monoplane. Cessna was convinced that a monoplane, with its reduced drag, would offer significant performance advantages over the biplane. In 1926, after Cessna had designed and built a high-wing monoplane, Beech agreed that Travel Air would produce the monoplane. Before long, a fleet of Travel Air 5000 aircraft, a high-wing, strut-braced, enclosed-cabin, 4-passenger monoplane, was ordered by National Air Transport company for their mail and passenger routes. Other airlines soon followed suit. The highly efficient Travel Air 5000 became the first commercial aircraft to cross the Pacific Ocean in July 1927.

Clyde Cessna had, for some time, been unsuccessful in persuading Beech to develop a monoplane. Cessna was convinced that a monoplane, with its reduced drag, would offer significant performance advantages over the biplane. In 1926, after Cessna had designed and built a high-wing monoplane, Beech agreed that Travel Air would produce the monoplane. Before long, a fleet of Travel Air 5000 aircraft, a high-wing, strut-braced, enclosed-cabin, 4-passenger monoplane, was ordered by National Air Transport company for their mail and passenger routes. Other airlines soon followed suit. The highly efficient Travel Air 5000 became the first commercial aircraft to cross the Pacific Ocean in July 1927.

Cessna then wanted to develop a fully cantilevered monoplane which would provide better performance than the strut-braced monoplane. When Beech and the Board of Directors rejected his idea, Cessna sold his Travel Air stock and resigned to start his own company in 1927.

With Cessna out of the picture, Beech, the only remaining member of the original three partners, became president and general manager of the Travel Air Manufacturing Company.

Air racing was not only a major spectator sport of the day, but it was a key means of establishing a company’s prominence over aviation competitors by demonstrating exceptional reliability and performance. One of the major events of the time was the National Air Races held in Cleveland, Ohio.

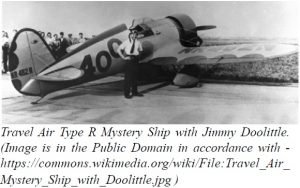

Travel Air designers Herb Rawdon, Ted Wells, and Walter Burnham, set out on their own time to develop an airplane that could outperform all known possible competitors. With the design in hand, they convinced Walter Beech to build the aircraft in the company’s shops. The Travel Air entry to the 1929 event, from its inception, was hidden from the press, who usually had access to, and did extensive articles about the new aeronautical innovations employed to win the races. The restricted access resulted in the press labeling the Travel Air racer as the “Mystery Ship,” and the name stuck. The Type R (“R” for Rawdon, aka the Mystery Ship) went on to win the Thompson Cup Race – the first time in air racing history that a civilian airplane “outraced” the military entries. Other variants of the Travel Air racer set numerous records for both pylon and cross-country racing and were considered to be the most advanced aircraft of the day.

Travel Air designers Herb Rawdon, Ted Wells, and Walter Burnham, set out on their own time to develop an airplane that could outperform all known possible competitors. With the design in hand, they convinced Walter Beech to build the aircraft in the company’s shops. The Travel Air entry to the 1929 event, from its inception, was hidden from the press, who usually had access to, and did extensive articles about the new aeronautical innovations employed to win the races. The restricted access resulted in the press labeling the Travel Air racer as the “Mystery Ship,” and the name stuck. The Type R (“R” for Rawdon, aka the Mystery Ship) went on to win the Thompson Cup Race – the first time in air racing history that a civilian airplane “outraced” the military entries. Other variants of the Travel Air racer set numerous records for both pylon and cross-country racing and were considered to be the most advanced aircraft of the day.

The success of the -5000 transport led to the 5-passenger improved and slightly larger Model-6000 in 1928 which served the National Air Transport company well in its growing airline business. However, the good times were about to end.

Travel Air had its peak year in 1929. By that time the company had 650 employees working two shifts in a state-of-the-art aircraft production facility, rolling out up to 25 airplanes per week. But sales slowed significantly just before the Great Depression wiped out much of its customer base.

By the end of 1929 the Travel Air Manufacturing Company had merged with the Curtiss-Wright Corporation. The Travel Air Division joined Curtiss-Wright’s other airframe manufacturing divisions which included the Curtiss-Caproni, Keystone, and Leoning Divisions as well as the Wright Aeronautical (engine) Division and the Curtiss Propeller Division. Beech, serving as a vice-president directed operations of the new company’s Wichita and St. Louis plants.

At Travel Air during the mid-to-late 1920s, Olive Ann Mellor learned the business from the ground up, handling correspondence, maintaining records, conducting transactions, and managing the office. She was quickly promoted to office manager and secretary to Walter Beech, in recognition of her financial and business insight. In February 1930, after the Curtiss-Wright/Travel Air merger, Walter Beech and Olive Ann were married.

At Travel Air during the mid-to-late 1920s, Olive Ann Mellor learned the business from the ground up, handling correspondence, maintaining records, conducting transactions, and managing the office. She was quickly promoted to office manager and secretary to Walter Beech, in recognition of her financial and business insight. In February 1930, after the Curtiss-Wright/Travel Air merger, Walter Beech and Olive Ann were married.

Beech was then appointed president of the Curtiss-Wright Corporation and the couple moved to New York in 1931 so that he could carry out his new responsibilities. However, Walter found that being an executive of a large corporation did not provide the satisfaction that he got from his hands-on involvement in the design and production of aircraft. Beech resigned from Curtiss-Wright in 1932 and Walter and Olive Ann returned to Wichita to start the Beech Aircraft Company – a bold move during the darkest days of the depression. Walter Beech would be the president and his wife served as secretary-treasurer.

Working in a small rented factory, Walter, Olive Ann, engineer Ted Wells, and a small group of employees set out to design and build the first Beechcraft airplane. The product of that effort was a single-engine, fixed landing gear, enclosed-cabin, “negative-staggerwing” biplane, designated the Model 17. Its first flight was on November 4, 1932. The performance of the Model 17 exceeded expectations, and it later won the 1933 Texaco Trophy Race.

Working in a small rented factory, Walter, Olive Ann, engineer Ted Wells, and a small group of employees set out to design and build the first Beechcraft airplane. The product of that effort was a single-engine, fixed landing gear, enclosed-cabin, “negative-staggerwing” biplane, designated the Model 17. Its first flight was on November 4, 1932. The performance of the Model 17 exceeded expectations, and it later won the 1933 Texaco Trophy Race.

As demand for the Model 17 increased, improvements were made that included a retractable landing gear and more efficient engines. The airplane was sleek, comfortable and fast and, as the economy slowly began to recover, the “Staggerwing”, as it was unofficially known, became the epitome of executive airplanes in the 1930s.

As demand for the Model 17 increased, improvements were made that included a retractable landing gear and more efficient engines. The airplane was sleek, comfortable and fast and, as the economy slowly began to recover, the “Staggerwing”, as it was unofficially known, became the epitome of executive airplanes in the 1930s.

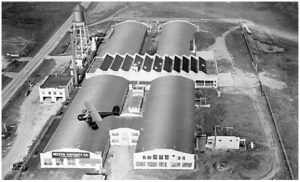

In 1934 in order to handle the growing production, the company was moved to the larger old Travel Air facilities which became Beechcraft’s permanent home.

As World War II loomed, demand for variants of the Beech Staggerwing grew. Orders from U.S. and foreign military services poured in and, before production of the type ceased in 1948, nearly 800 had been built. Reflecting its classic and graceful lines, several recent surveys have named the Beech Staggerwing among the world’s top ten most beautiful aircraft.

By late 1936, the company issued common stock and changed its name to the Beech Aircraft Corporation. With a growing order list and sufficient funding reserves, Beech was able to invest in the development of a new aircraft. The all-metal Twin Beech Model 18 was designed to serve as an executive transport or to meet the needs of feeder airline businesses. Its outstanding performance was demonstrated by pilots Walter Beech and H.C. Rankin by winning the 1,084-mile non-stop Macfadden Trophy race from St. Louis, Missouri, to Miami, Florida, at an average speed of 234 mph.

During World War II large numbers of Beech Model 18 variants served as multi-engine, bombardier and navigator trainers, executive and utility transports, and ambulance transports. By the time production of the Model 18 family of airplanes ended in 1969, over 9000 Twin Beech aircraft had been built.

During World War II large numbers of Beech Model 18 variants served as multi-engine, bombardier and navigator trainers, executive and utility transports, and ambulance transports. By the time production of the Model 18 family of airplanes ended in 1969, over 9000 Twin Beech aircraft had been built.

In addition to the production of variants of the Staggerwing and the Model-18 during the war, Beech developed the AT-10 twin-engine trainer using wood instead of scarce aluminum that would be needed for the military’s fighters and bombers. The Beech company also produced parts for troop carrying gliders and other military aircraft.

Walter became seriously ill in 1940 and he was hospitalized for nearly a year. The responsibility of leadership at that critical time fell to Olive Ann, who skillfully steered the company through a period of rapid growth. Employment at the company climbed from 235 in 1939 to over 4000 by 1942. Before the war ended, Beech employment exceeded 14,000 workers.

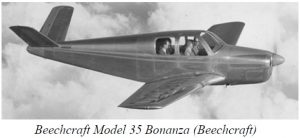

As the war was coming to an end, Beech again turned his attention to the civilian market. In addition to producing a commercial version of the Model 18, a single-engine, 4-place, V-tail general aviation was designed and first flown in December 1945. Certification of the Model 35, known as the Beechcraft Bonanza, was obtained in 1947 and it sold well. Production of the Model 35 series did not end until 1982.

As the war was coming to an end, Beech again turned his attention to the civilian market. In addition to producing a commercial version of the Model 18, a single-engine, 4-place, V-tail general aviation was designed and first flown in December 1945. Certification of the Model 35, known as the Beechcraft Bonanza, was obtained in 1947 and it sold well. Production of the Model 35 series did not end until 1982.

Walter Beech, however, did not live to witness the success of the Bonanza. He died suddenly of a heart attack on November 29, 1950.

Following Walter’s death, Olive Ann was elected president and chairman of the board. Under her guidance, Beechcraft continued its expansion and diversification. While she was in charge, the company developed a series of new aircraft including the Queen Air, the Debonair, the Baron, and the King Air and entered the space age with the production of a number of missile systems. Beech also teamed with other major aerospace companies to produce assemblies for aircraft and helicopters.

Following Walter’s death, Olive Ann was elected president and chairman of the board. Under her guidance, Beechcraft continued its expansion and diversification. While she was in charge, the company developed a series of new aircraft including the Queen Air, the Debonair, the Baron, and the King Air and entered the space age with the production of a number of missile systems. Beech also teamed with other major aerospace companies to produce assemblies for aircraft and helicopters.

Olive Ann stepped down as president in 1968 and fully retired from the position of chairman of the board in 1982. She died on July 6, 1993, at the age of 89. Over its long history, in peace and war, Beech Aircraft built more than 50,000 airplanes and set many speed and distance records. Not a bad legacy for a company run by a man who never got past the sixth grade and a woman trained as a secretary and bookkeeper.

Walter Beech held a Transport Pilot Certificate and had logged more than 10,000 hours in the air. He was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1977 and the International Aerospace Hall of Fame in 1982.

Olive Ann Beech was awarded the Wright Brothers Trophy in 1980. She was enshrined in the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1981 and the International Aerospace Hall of Fame in 1995. The only other couple in the National Aviation Hall of Fame is Charles and Anne Lindbergh.